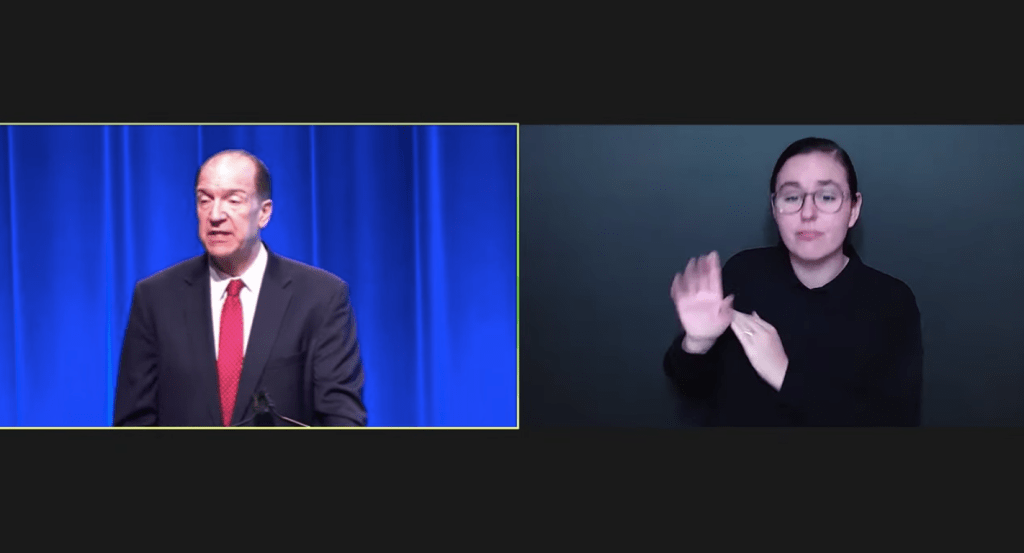

Taking place on May 25-26th in a hybrid format with delegates from around the world, the World Bank Youth Summit was an important event for two reasons. First, it came after a decade of existence, celebrating the gains made during those years, and second, it occurred during a period of polycrisis, in David Malpass’ words, a time when international community resilience has been tested. Themed “From the Ground Up: Local Solutions to Drive Global Impact,” the Summit sought solutions for some of the world’s most vexing problems from the ground up. From fragility, conflict, and violence to climate change and energy transition to jobs and skills, young people from all over the world contributed their insights and knowledge.

In his opening remarks, President David Malpass emphasized the magnitude and scale of the crisis facing the world of development today. In focusing on the FCV setting in particular, Mr. Malpass pointed out that the Sahel region is fragile, as illustrated by his recent visit to Niger and the ongoing political crisis in Sudan. Another issue that was addressed by the President was the mismatch between jobs and skills. Malpass explained that mismatch of skills was a major concern for the Bank, and that an ongoing apprenticeship program in Kenya demonstrated the bank’s response to this issue. While these issues are pertinent to everyone and exist in all countries (developed and developing), they are most prevalent in developing countries, where youth pay the highest price. Nevertheless, the youth have not been passive, according to Ousmane Diagana, Vice President of the World Bank for West and Central Africa. Diagana disclosed that the youth had utilized their creative and energetic abilities to meet these challenges head-on, with the Covid-19 interventions serving as an example. Mamta Murthi (Vice President for the Bank’s Human Development) emphasized that this is especially important in the developing world, where the young population dictates that solutions must never be developed in isolation, but in collaboration with them.

Yet, the scale of these challenges proves more challenging than the combined response of the youth, especially those who are most vulnerable. According to Zenna Law, who shared perspectives from Malaysia, jobs are increasingly precarious for migrants in Malaysia, which is combined with high acquisition costs for a population already facing structural challenges. This calls for more concerted effort by the Bank to extend beyond just the supply economics that seems to dominate its business to something more substantial. As an example, Mamta Murthi revealed that the bank (the largest financier of education in the world) goes beyond providing schools and teachers with equipment, and also actively participates in the demand side by conducting upskilling programs, including traditional skilling programs such as those in West Africa as well as the new digital economies, also known as gig economies. In Murthi’s view, this kind of engagement is crucial as it allows the Bank to influence the future of work. However, she also believes that there is more to be done, urging the youth to continue the conversation because she believes the only way for the Bank to replicate progress is through cross-fertilization of ideas. To what extent such ideas are helpful, and for whom remains at large. Putting aside the validity of this claim for a minute, I think upskilling is also an attempt to right the wrongs. After decades of disappointing development showdowns, the Bank is under immense pressure to get things right.

With upskilling as the elephant in the room, Deloitte’s Sofyan Yusufi challenged the participants that “development for the poor does not have to be done poorly.” A clarion call for enforcing talent in such a challenging context or so it should be understood. Nonetheless, one Nigerian participant suggests that we may need to move beyond the rhetoric of upskilling to investigate the Bank’s mechanics for bringing about positive change in the development sector. The elephant in the room, in the opinion of this participant, is not just the lack of talent or the lack of preparation of youth to face the challenges, but rather how the Bank conducts its business – by favoring the government as its primary client at the expense of youth. This sentiment was well received by participants in Washington, D.C., and I am certain of most online participants as well.

As a matter of fact, this has been one of the Bank’s long standing criticisms. Bank policy dictates that it lends to governments in developing countries which then (most of the time) misuse these loans for non-developmental purposes, leaving the youth with what Noris Moreno (speaking for Venezuela) described as ‘learned helplessness,’ where societal benefits are hard to come by. Moreno explains that as the youth flee weak political economies in the global south, they are confronted with severe institutional barriers in their preferred destinations (primarily industrialized norths), thus associating hopelessness with nature. Heela Yoon, speaking for Afghanistan, makes a very well-crafted proposal that World Bank projects in fragile settings should have a long-term orientation so as to address the systemic problems that underlie underdevelopment in such settings. For Yoon, doing a project to prove relevance in the development context hasn’t worked and needs to be changed.

Overall, the conference was a great success. In spite of the fact that most of the sessions were well-presented, the career session was my favorite. In fact, it was extremely difficult for me to decide between the World Bank Young Professional Program (the famous YPP), and the much-recent United Nations Young Professional Program (UN YPP). Since I wish to pursue a career at the United Nations in the future, I chose the latter option. It did not disappoint me, especially after listening to Mahmoud Almasri, one of the current UN YPPs, who generously shared his insights with us. According to Mahmoud, one reason for the underrepresentation of certain developing countries (mainly FCV) in the United Nations is that there are insufficient applicants from these countries. In view of the fact that most of the citizens are already in a disadvantaged position information-wise and in other areas, it was not a huge surprise to learn that such was indeed, a factor. Nonetheless, it was rather reassuring to learn that the UN had considered a YPP program for these countries. Considering that the UN has a reputation as a bureaucratic ecosystem, such constitutes an institutional innovation.

Last but not least, I found the online engagement less enjoyable than I had anticipated. Next year, I must be in the room – physically, that is! Ahaha.